Beatitudes – my last ever sermon, aptly at Brighton College

Thank you for having me, it is great to be amongst you again.

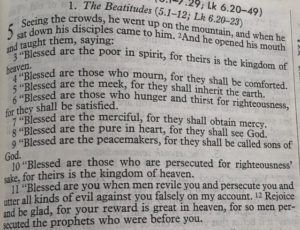

I’ve been a Christian since I was young, and I’ve known these famous words just read to us (called the Beatitudes) as long as I can remember. But when Father Robert said that it was the reading for today, I nearly declined his very kind invitation to speak. Not because I do not love these words – they are indeed beautiful. But they are also difficult words. Some of the Beatitudes are easy to hear wrongly. Hard to understand. How are the poor in spirit, the grieving, the persecuted ‘blessed’? How can I stand here and talk about that? (Especially when I don’t have first-hand experience of poverty, pain or persecution.) So I nearly said no. But then, as I dwelt on these words, something dawned on me. That I don’t think would have been able to articulate a year ago without your help. So I thought I would share that this morning in case it was helpful.

I will come to that thought I had in a moment. But first of all I want to be clear what the Beatitudes are not saying. They are not saying: “it is good to suffer in this life because when you die and go to heaven you will be blessed.” That interpretation is not only bad theology. But it is dangerous too.

Firstly, because it is open to abuse. It can imply that suffering, as such, is a good thing. And justify passivity in the face of suffering. No suffering, of any kind, is good in itself. Secondly, that interpretation – ‘suffer in this life and you will be blessed when you go to heaven’ – is bad theology. Jesus’ teaching about heaven was not of a distant reality after death, but a present reality, that not even death can contain. Something to experience here and now. Even as we await its fulfilment when he returns. What Jesus is expressing in these words is that people in these situations – poverty of spirit, grief, persecution, those literally hungering and thirsting for justice, peace, mercy. These people in these situations, are blessed here and now. NOT because any of these sufferings are good in themselves, or justifiable, or anything like that. BUT because of this present reality Jesus spoke about and came to make known. He called it called heaven – What God’s presence is like, here and now.

So what does “blessed” look like? How can we make sense of it, when it is said of people who are suffering loss, or persecution, or hungering and thirsting for justice in this world. What struck me as I thought about the Beatitudes and potentially speaking on them. Is this thought: They only make any sense in the context of relationship.

As just words, many of them sound like oxymorons. Contradictions in terms. Blessed are the poor, those who mourn, those who are reviled, persecuted… How are those things blessings? These phrases can sound like contradictions. But, in the context of relationship, a profound truth emerges. It is a truth that doesn’t answer all the questions. But it is no less real for that. (In fact, as a scientist I would say that the test of a true statement about reality is that it calls forth more questions rather than closes them down.)

The truth Jesus is speaking about is that relationship is the only thing that can transform bad stuff into the most precious of situations. (I cannot emphasise enough how much I am not saying that in anyway the bad stuff is therefore OK in itself. I am talking about a transformation – not a justification – that happens in the context of relationship.)

Let me illustrate with a ‘Beatitude’ that I could not have articulated a year ago. And certainly not without your help: “Blessed are those diagnosed with MND, because they will discover a love and a care for them that they did not know was possible.” I have you all to thank for showing me that. The words alone “blessed are those diagnosed with MND” are a contradiction in terms. I would so so love to be free of it. Is it a blessing? No. Never. Am I blessed in the midst of it? Yes. And only because of relationship. The kindness and love you showed me when I stepped down transformed not only my experience of being ill. It changed how I thought about myself. Negativity that I had about myself, which I thought would always be part of me, was taken away.

Jesus called this dynamic, this transforming reality, the Kingdom of Heaven. In John’s gospel he calls it simply Love. He said that he had come to be its foundation – the logic, the means ultimately – for this present reality to be just the beginning of a life that even death cannot destroy.

The second beatitude “Blessed are those who mourn for they will be comforted” means a lot to my sister this year. In January, she gave birth to a baby – James – who sadly died in labour. We knew he was very poorly but we had hope that he would live. My sister mourns his loss. But if you ask her whether James was a blessing in her life she wouldn’t hesitate to answer yes. My niece, Imogen, who is 5 will always have a brother. As a family they will always cherish the nine months that they had him alive with them during the pregnancy. Does she mourn? Yes, every day. Is she blessed? Yes, every day.

The blessing is only because there is a relationship that transcends the grief. James will always be James. Her son, Imogen’s brother. Imogen built a bond with him through talking to him through my sister’s tummy. Imogen said to me the other day that his favourite colour was pink (which co-incidentally is her favourite colour!).

Relationship is the only way for my sister’s family to say “Blessed are those who mourn.” And as a Christian, I believe that a relationship with God is the ultimate context for these Beatitudes. The present and a future reality that Jesus spoke about, founded upon his death and resurrection.

To sum up. The Beatitudes do not answer the all questions of suffering. They certainly are not licence for us to justify suffering as somehow good in itself. Nor are they permission to leave people in suffering. Or to offer easy words about the nobility of enduring pain.

What they are is an invitation for us to make them real, as you did for me, through relationship. It is through relationship that the Beatitudes are no longer a contradiction in terms: Being a comfort to those who mourn, so they can say, “Blessed are those who mourn”; Being justice and peace bringers to those in our world who are enslaved, persecuted, poor, so that they can say “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied”

I think that until Jesus returns there will always be a degree to which we cannot fully explain these words. I couldn’t bear it if you thought I was trying to explain away suffering. Or answer too neatly questions about faith, God or the nature of this world. All I know is that in these Beatitudes I find a reality about human, and ultimately God’s, love that makes it possible to hold in tension some of these difficult things. As I say, I have you to thank for helping me to grasp a better sense of their truth.

So as you read the Beatitudes – I would encourage you that if you are mourning, if you are hungering for justice in this world, peace, a vision of God – any of these things mentioned by Jesus. You can know that you are blessed even before that stuff gets fully resolved. Through relationship. Communities like this one. And ultimately through the love of God – the relationship that he brings – through Jesus Christ. Amen.

Gracious God,

Help us to find blessing in every season of our lives, through discovering the transforming beauty of relationship – in communities like this one, and ultimately through your presence with us. In Jesus name, Amen.